Lenguaje, Gramática y Filologías

Verbs of change of state

4º Filología Inglesa. English VP Analysis.

INTRODUCTION

ABOUT THE WORK ------------------------------------------ 3

FIRST PART

lexical entries, alternations and other features observed in verbs of change OF state. ------------------4

SECOND PART

TYPES OF VERBS. --------------------------------------15

THIRD PART

what kind of “change” these verbs show? ----------19

discussion and conclusions -------------------20

notes ---------------------------------------21

Introduction

The present work began with the meeting of their two authors: they only knew that “break” was a verb of change of state. From this verb they had to use their common sense together and find some more verbs that were alike to “break”, denoting a clear change of state in their meanings.

With their teacher's help, they selected some verbs that belonged to the break category (as burn, change, crack, decompose…) and rejected others that didn't (as cut, born or mix).

Then, they started analyzing some of the mentioned verbs of change of state and little by little discovered differences and similarities among them. The sentences used as examples have parts, which are underlined; these parts are the analyzed ones. Everything into brackets is optional.

The work you have in your hands is in crescendo, that means, it shows the process of finding out the characteristics of these verbs in the same way that the authors did. In this way the reader not only discovers these verb's features at the same rhythm than the authors, but also sees more clearly the differences and similarities that appear.

The authors.

FIRST PART

lexical entries, alternations, and other features observed in change of state verbs

-

Break:

A- “Oh yes, if Greg had been around when the storm broke he'd have faced ruin”

B- “One of them broke the ban on Boris Pasternak's work”

In these examples the authors saw that we must be careful. In A we observed that break seems to select only one argument (“The storm”). Nevertheless, in B we could say that break selects two arguments (“one of them” and “the ban”).

In the first case, “the storm” would be the subject, and its semantic role: theme. In the second case “one of them” is the subject and the causer at the same time, and “the ban” would be the theme. So… are we talking about two different verbs “break”? :

Break <1> (THEME) Break <1,2> (CAUSER, THEME)

Obviously, something wrong is happening. After thinking about what exactly is the matter between these two sentences, we reached the conclusion that BREAK only selects one argument (always the THEME) and, what's more, this argument is not always the subject, so we do not have to underline it:

Break: <1>

<THEME>

[NP], [IP]

Which is the reason?… If we pay more attention to the examples above we can see that A fits perfectly in our conclusion, but… what about B? Yes, it fits, too:

One of them broke the ban The ban broke.

DO SUBJECT

As we see, the subject (whose thematic role is the causer) is only more information that we receive from the sentence, the verb does not select it, and it is not required by the verb.

Notice, however, that in sentence A the verb is not used in the same way than in sentence B; in terms of meaning they are not exactly equal. In the first example we could replace broke by a verb like explode for instance, although we are now going to the field of Semantics, which is not the area we are working in. But we wanted to highlight this difference because due to this lack of exact meaning and due to the presence of a natural element in the construction (“the storm” ) we can say:

The ban broke. One of them broke the ban.

But we cannot used the causative-inchoative alternation to show the causer of the “breaking” of the storm:

The storm broke *Someone broke the storm.

We can say:

The storm broke due to the bad weather. / Bad weather made the storm break.

But not:

* Bad weather broke the storm.

That happens because “break” is not used in this example as in the previous example. In B we are talking metaphorically.

-

DIE:

Now we easily see that break is a one-place predicate verb. So we looked at our notes from the English VP Analysis classes and we checked that “die” is a one-place predicate, too. And it also seems to involve an obvious change of state in its meaning (from life to death, end of life)… we decided to analyze it, in order to see if it worked in the same way. Let's see some sentences with the verb die:

C- “He was al Ibrox in 1971 when 66 fans died in a crush on the steps of the stadium…”

D- “Sands (proper noun) died soon after his election…”

Both sentences have an easy-to-see subject, C: 66 fans; D: Sands. But the thematic role could be a bit confusing: are the subjects the EXPERIENCERS (of their own deaths) or are they the THEMES? At this moment we reviewed these two concepts:

-

Experiencer: The entity that experiences some (psychological) state expressed by the predicate.

-

Theme: The entity undergoing the effect of the action expressed by the predicate.

We can see that between the two terms exist similarities, so it is not strange that we could confuse them. Anyway the one that seems more obvious for the verb “to die” is the THEME. So we can assert:

Die: <1>

<THEME>

However, some differences between die and the previous verb (break) are manifested. We could say:

One of them broke the ban The ban broke.

But we cannot say:

66 fans died *The crush died 66 fans.

Why? At first we didn't know the answer. And that happened because we only looked to the lexical entries of each verb. We discovered later that we must look at something else: the alternations each verb allow.

From this new aspect is not difficult to see the cause of the mentioned difference between die and break: break is an ergative verb that can be used with the causative/inchoative alternation:

Causative: One of them broke the ban / Inchoative: The ban broke.

CAUSER THEME THEME

While it does not occur with die, as we have seen already:

*The crush died 66 fans. 66 fans died.

THEME THEME

Notice, nevertheless, that in Spanish or Catalan happens the same:

*La aglomeración murió 66 fans. 66 fans murieron.

* L' aglomeració va morir 66 fans. 66 fans van morir.

And also in German:

*Das Gedränge starb 66 Personen. 66 Personen starb.

That happens because die does not allow this kind of alternation, what means that it is not an ergative verb. In its place we'd have to use “kill” for the English sentence “matar” for the Catalan and Spanish constructions and “töten” for the German one.

At the same time, we can also observe that the lexical entry of this verb is still stricter with its selection of arguments. The unique argument that die selects is, as we have explained, the theme in the subject position. But we have to expand that lexical description asserting that this THEME has to be always an

animate one (unless you are talking abstractly or metaphorically). You can say perfectly:

Plants die.

George died (last week).

But it would be wrong to utter:

The table died.

The wall died.

Sometimes a metaphorical tone is given to the sentence, for example we can say:

Languages die.

Traditions die.

And they are completely grammatical, but the reader must take into consideration that we are using die with a difference from the original meaning… we could replace both example verbs by disappear , for instance.

All ergative verbs have the causative-inchoative alternation, and also allow the middle construction (but not in the other way round). In this way we can say:

Causative Inchoative Middle

One of them broke the ban. The ban broke. This ban breaks easily.

*The crush died 66 fans. 66 fans died. *Fans die easily.

So, these examples offer us the answer: Die is not an ergative verb because it cannot appear in the causative-inchoative alternation form, and neither the middle.

-

BURN:

E- “If the metal is too thin (…) it will burn.”

F- “London burnt in 1600s…”

In E and F we can see that both subjects (it and London) have the semantic role of THEME. Let's see if burn works in the same way as break or not:

The ban broke. One of them broke the ban.

THEME CAUSER THEME

The metal will burn. I will burn the metal.

THEME CAUSER?AGENT? THEME

Is “I” the CAUSER or the AGENT of burn? The answer is that this subject is the causer so this verb is very similar to break, which also selected only one argument (the THEME) and it had not to be underlined because it is not always the subject (the same case as “the metal” as we have already seen):

Burn: <1>

<THEME>

[NP], [IP]

If “I” is the CAUSER and not the AGENT, we are dealing with a verb that has the causative-inchoative alternation. The middle construction for this new ergative verb would be:

Thin metals burn immediately. / Metals burn slowly. / This metal burns easily. / etc.

But the authors of this work checked that something can burn and that someone can make burn something: “metals burn” / “I burnt these metals”; but you can burn someone, too. Do the semantic roles change then? Let's see it:

-

“If she accosts me again, (…) I'll burn her!!” She will burn.

CAUSER THEME THEME

We think that the sentence that results, is correct, although we consider that the following sentence would be more adequate and precise:

-

She will be burnt (by him). -Using the passive form.

We need not a reflexive form unless the subject itself is the causer of his/her own act of burning:

I burnt myself (with my own cigarette).

Causer THEME

Nevertheless, if we are talking about a different context the semantic role of the subject WILL change:

John burned on the beach last weekend.

THEME LOCATION

The meaning changes slightly, but we are not talking about two different verbs “burn”, we are exposing different ways of burning.

-

DECOMPOSE:

G- “The molecules have an extremely stable structure and do not readily decompose into hydrogen and oxygen”

H- “… There is a great danger of massive overdose if the packages decompose in the intestinal tract.”

Compare G and H with the next examples:

- The ban broke. One of them broke the ban. (Ergative).

- The packages decomposed. *Someone decomposed the packages.

- Molecules decompose (into hydrogen and oxygen). *Susan decomposed molecules.

In the sentences above it seems to be clear that decompose does not accept the causative-inchoative alternation. But what's the matter with non-animate subjects?:

- Hydrogen and oxygen decompose molecules.

- Drugs decomposed her intestinal tract.

In this case the sentences are perfectly grammatical. We can affirm, in consequence, that this verb only selects non-animate beings as CAUSERS.

The middle construction for decompose is:

- “Molecules decompose easily (into hydrogen and oxygen)”.

- “Packages decompose rapidly (in the intestinal tract)”.

So the lexical entry for this verb is:

Decompose: <1>

<THEME>

[NP], [IP]

-

DRY:

I- “Sam dried the sweetcorn.”

J- “I quickly stood up and dried my eyes.”

Here we can observe that occur the same as in previous examples: The subjects (Sam and I ) seem to be the agents, but they are not: they are the CAUSERS. It is easier to see it in the next example:

-The sun dried the corn.

The sun cannot be the agent because it has not intention of doing anything: the result is unintentional, and what's more, the agent has to be animate.

Dry is used with the causative-inchoative alternation, compare it with the verb crack, which allows this kind of alternation, too:

-“… my friend cracked an egg in a bowl.” “The egg cracked (in the bowl).”

CAUSER THEME THEME

-“I dried my eyes.” “My eyes dried (when time went by/when I saw him…).”

-“Sam dried the sweetcorn”. “The sweetcorn dried (in the sun).”

The lexical entry for “dry” will be:

Dry <1>

<THEME>

[NP], [IP]

It is very curious that a verb which is so similar in terms of spelling to die, is at the same time so different in terms of lexical characteristics. We can make the following construction:

-

He dried himself.

But, notice that only extracting a consonant the sentence is ungrammatical:

-

*He died himself.

We would have to use “kill” to make the sentence grammatical or use a verb like “suicide”. Some verbs require features that others don't, regardless their similarities in spelling.

-

GROW

The authors of this work had to be very careful at the time of discovering what were the semantic roles of the elements (constituents) of the sentences. For example we can see that in:

- Mary broke the vase.

“Mary” is the CAUSER, but it doesn't mean that all the information that fulfils this subject position in every sentence will be the causer. In the sentence:

- Henry broke his leg.

Obviously the subject hasn't the thematic role of CAUSER, but of EXPERIENCER.

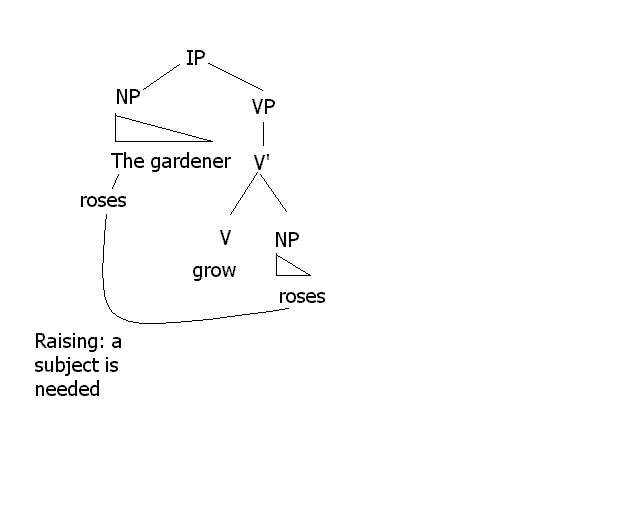

In this way, we found a verb that could have more than two thematic roles in the subject position without altering its meaning but depending on different contexts. This verb is “grow”. Looking at the examples the reader will see what we mean:

a)The gardener grows roses.

CAUSER THEME

Grow <1>

<THEME>

b) Roses grow nicely.

THEME

Grow <1>

<THEME>

c) Peter grew a foot.

experiencer measure

Grow <1, (2)>

<EXPERIENCER, (MEASURE)>

“Grow” selects one complement in a) and b). In b) the surface structure tells us that they are different, but the deep structure shows that “roses” is a complement of the head “grow”.

Grow <1>

<THEME>

[NP], [IP]

SECOND PART

TRANSITIVES OR INTRANSITIVES? ERGATIVES, UNACCUSATIVES, UNERGATIVES? ANALYSING THESE CHARACTERISTICS IN VERBS OF CHANGE OF STATE.

In this part of our work we are going to see what type of verbs are some verbs of change of state. In order to make easier our aim, we are going to deal with new verbs, in order to see more examples of this sort of verbs, to add more information to the present work, and avoid being reiterant. Nevertheless, the authors perhaps allude to some previous verbs, if necessary, to clarify their explanations or contrast differences.

-

CHANGE

K- “Names have changed to protect the privacy of those involved.”

L- “His musical tastes changed radically”

What type of verb is “change” in these two examples? Let's see some necessary characteristics for specific types of verbs in order to discover it. Is it an unergative verb? If so, it has to select an agent… clearly “names” and “his musical tastes” are not AGENTS, but THEMES. So unergatives discarted. The function of both themes is the function of subject.

It is more probable that “change” functions as an unaccusative in examples K and L, but we must test it. These are the reasons (prerequisites for the unaccusatives):

- It does not select an AGENT, but a theme.

- It is very similar to passive constructions.

- In the examples is used as an intransitive verb.

-

The themes are the subjects in the sentence (a characteristic that is not necessary if we are talking about unacussatives).

Indeed, “change” assigns unaccusativity in both sentences… but we must look at other examples so as to confirm if it could work as something else in other kind of constructions:

M- “He changed his mind.”

N- “She will change it”

M and N show us a big difference in construction in relation to K and L, here “change” is used as transitive. the question now is to guess what type of transitive verb it is… how much arguments does it require? The answer is one: the THEME (lexical entry), so “change” has in these two sentences two arguments but only one required: we are talking about a one-place predicate

(argument selection) and, as we deduce by thinking in its syntactic functions, about a monotransitive verb (surface syntactic functions).

When used in this way, this verb of change of state has the possibility of appear in the causative-inchoative alternation form, as most of the mentioned ones in the first part of our work (except “die” ):

- “He changed his mind.” His mind changed.

- “She will change it.” It will change.

And the Middle construction will be (e.g):

-His mind changes rapidly. / Mind changes easily, etc.

In consequence, and taking into consideration all these aspects, it is obvious that functioning as a transitive verb, “change” is an ergative verb.

Let's see if it happens the same with the next verb of change of state:

-

FREEZE

O- “Chantal's expression froze.”

P- “The boy froze.”

From these two examples we can affirm immediately that “freeze” assigns here unaccusative, too, because it follows all the previously mentioned pre-requisites (the same as “change”). But, does it work also in the same way as “change” in other type of constructions or it has no possibility of other constructions? Two more examples are provided to verify that aspect:

Q- “She froze her face.”

R- “The wind just froze my balls.”

Here “freeze” is used as a transitive verb where the subjects have the thematic roles of CAUSERS and the Direct Objects of THEMES. In O and P we saw that the subject positions were occupied by themes, so we easily deduce the lexical entry of “freeze”, which is the same of all the analyzed ones in the First Part of our work (except, as we have said already, “die”). So we are talking about an ergative verb again: it works also with the causative-inchoative alternation and with the middle construction.

Having checked already all these aspects let's see what happens with the verb that is different from the rest from our study. The same sentences are going to be used in order to the reader to expand the information about it. The verb we are talking about is “die”.

-

DIE

- “He was al Ibrox in 1971 when 66 fans died in a crush on the steps of the stadium…” (iii)

- “Sands (proper noun) died soon after his election…” (iv)

In the First Part of the present work, the authors analyzed this verb and affirmed after the necessary checking that it is not an ergative verb. So which type of verb is “die”?

We also saw that this verb is impossible to use followed by a Direct Object (it can not appear in transitive constructions). That means that it has to function always as an intransitive verb. Having discovered this, we found that this verb accomplishes all the requirements that we mentioned about the unaccusatives: “Die” is UNACCUSATIVE, and it is the only verb of all our work that functions as it does (only as an intransitive one). Remember:

-Sands died. / He died.

But impossible to utter:

-*The criminal died Sands. / *The criminal died him.

THIRD PART

What kind of “change” these verbs denote?

Classification according to the type of change of state that the verbs mean (some new verbs have been included in order to get the similarities they semantically share):

-Internal

-DECOMPOSE

-External

-Dual :

A) Depending on the context will belong to the “internal” or the “external” group: it can be used with both meanings, but only with one of them every time:

-CHANGE

Internal: She changed her mind.

External: She changed her old car.

-BREAK

Internal: You broke my heart. (Metaphorical)

I broke my arm.

External: George broke the lamp.

B) The change of state is both appreciable internal and externally and at the same time:

Apart from this, probably we could create an imaginary line to delimit the meaning of these verbs of change of state into groups with similar features :

Breaking verbs:

- crack, break, crash, explode…

Verbs that mean that an entity changes in its form:

- burn, freeze, melt, (explode), decompose…

Verbs that involve in its meaning a transformation:

- Complete transformation: die, grow…

- Partial transformation: dry…

Abstract change:

- marry

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

All the analyzed verbs of change of state are practically equal in terms of lexical entries and functioning both with transitive and intransitive constructions. The exception to all of them is “die”, which only works with intransitive constructions.

We can affirm, consequently, that the majority of verbs of change of state are ergatives, although there is a little part of them which are only unaccusatives (as “die”).

Regardless the mentioned homogeneity, it exists also slight distinctions among all the verbs of change of state. We have tested this characteristic by classificating all of them into different groups and analyzing their exact meaning in terms of the change they denote. It was not our main purpose, but, at the end, Semantics has been included also in our explanations in order to feed our work and exploit all the interesting aspects some verbs of change of state gave to us.

We must comment also that at the beginning of this research, the authors prepared ourselves to find certain phenomena, that is, they foresaw some hypotheses that have not been confirmed. For example, they thought they were going to find some verbs that, due to their different meanings, had to be split into two different verbs (= spelling = meaning), but it had not occurred with the verbs we have analyzed.

The students also expected to find very different semantic roles selected by the verbs, and, it has been in this way (we expected some agents, though), a clear example of that are the verbs “break” or “grow”.

We have learned also that we must not take into consideration the similarity of some verbs in their spelling: they can be absolutely different and these two aspects are clearly separated (pronunciation from linguistic features). It is important to remember that “die” and “dry” differ only in a phoneme (pronunciation) and they worked in completely different ways.

It is not ungrammatical but, as the Middle Construction shows a general property, it wouldn't be acceptable in most of the cases and contexts. A similar example of this would be a sentence that appeared in class: “Children drown easily”. But perhaps it would work with more information: “Fans die easily when they see their favourite singer and have no enough air to breath in the concerts.”

In fact, we have seen in class the relationship between the passives and the unaccusatives.

From last year's class notes.

We think that the results are not needed at this point of the work. They would be pretty redundant (we have lots of examples about causative-inchoative alternations and middle constructions in the first part and just before “freeze”, too).

If we refer to corporal decomposition in dead persons, we must not leave unsaid that this decomposition is visible (external) after a period of time.

Idea created from a distinction of last year's class notes where Tenny distinguished among: verbs of Change of Physical State, of Consumption and Creation, of Abstract Change of State, of Motion and of Achievement.

VP Analysis

Verbs of Change of State

2

NOTES. QUOTATIONS EXTRACTED FROM

i- Folly's child. Tanner, Janet. London: Century Hutchinson, 1991, p.13.

ii- [Daily Telegraph, electronic edition of 19920412]. London: The Daily Telegraph plc, 1992, Arts material, pp. ??.

iii- Esquire. London: The National Magazine Company Ltd, 1993, pp. ??.

iv- Contemporary issues in public disorder. Waddington, D. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul plc, 1992, pp. ??.

v- Excerpt from My favourite stories of Lakeland. Wyatt, John. Cambridge: Lutterworth Press, 1981, pp. 113-116.

vi- Bacons College: lesson (Educational/informative). Recorded on [date unknown] with 10 participants.

vii- The grail murders. Clynes, Michael. London: Headline Book Publishing plc, 1993, pp. 77-219.

viii- Sentence made up by the authors in order to exemplify the explanations.

ix- [Misc unpublished -- university notes]. u.p., n.d., pp. ??.

x- British Medical Journal. London: British Medical Association, 1976, pp. 9-513.

xi- Country Living. London: The National Magazine Company Ltd, 1991, pp. ??.

xii- Part of the furniture. Falk, Michael. London: Bellew Publishing Company Ltd, 1991, pp. 1-146.

xiii- Sentence made up by the authors in order to exemplify the explanations.

xiv- Brownie. London: Girl Guides Association, 1991.

xv- Charity leaflets and letters]. u.p., n.d., pp. ??.

xvi- The wedding present. Hodkinson, Mark. London: Omnibus Press, 1990, pp. 5-91.

xvii- The Daily Mirror. London: Mirror Group Newspapers, 1992, pp. ??.

xviii- Drama lecture (Educational/informative). Recorded on 18 November 1992 with 10 participants.

xix- Sons of heaven. Strong, Terence. Sevenoaks, Kent: Hodder & Stoughton Ltd, 1990, pp. 73-154.

xx- Frankie. Highsmith, Domini. London: Bantam (Corgi), 1990, pp. ??.

xxi- Jay loves Lucy. Cooper, Fiona. London: Serpent's Tail, 1991, pp. 11-154.

xxii- Leeds United e-mail list]. u.p., n.d., pp. ??.

-DIE -MELT

-BURN -DRY

-FREEZE -GROW

-EXPLODE

-CRASH

-CRACK

-MARRY

Descargar

| Enviado por: | El remitente no desea revelar su nombre |

| Idioma: | inglés |

| País: | España |